Paris was sleeping when I stepped out into the morning. The formerly glittering Eiffel Tower loomed dark in the sky. Even the most persistent souvenir vendor had long packed up his wares for the comforts of home, and so, for a moment, the streets belonged to me. I gave up my reign shortly as I descended underground to take the train to Versailles, where generations of kings named Louis held court. Our train slithered out of Paris into the wilds of the suburbs as the day sighed into being, bleary-eyed.

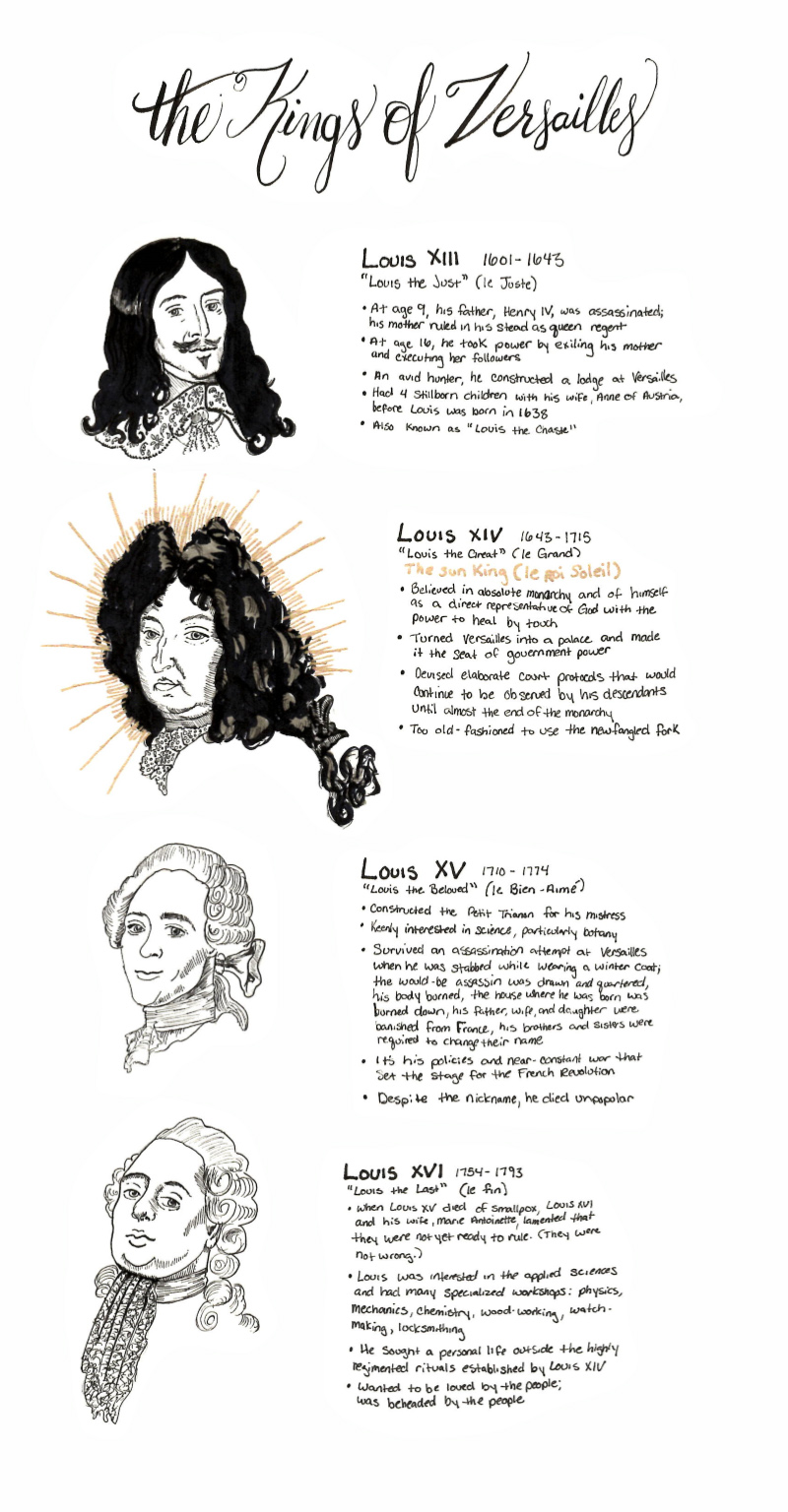

Even in the damp grey light, the gilding on the palace glowed. On a clear day, it must shine like the sun–what less, for the palace of The Sun King, benevolent giver of life, radiant and untouchable? We were among the first arrivals, and those of us there paid tribute to their fellow early risers by photographing one another in front of the gates and then leaving each other the hell alone, quietly massing at the entrances, waiting for the doors to open and trying to keep warm. There was a little jostling for position in line but upon entrance, the sheer scale of Versailles mocks the petty shuffling of individuals. Roughly twenty people dispersed into the building at its first unlocking to the public that day and rarely did I encounter another person during most of my visit. In the early morning, the palace is unnaturally quiet, far quieter than it would have ever been during the reign of Louis XIV and beyond. Louis XIV, affable but absolutist, needed a way to keep his courtiers in line: under his eye, unable to plot against him politically in Parisian establishments, bound to him financially. As such, in 1661, he began the process of transforming the hunting lodge of his father at Versailles, twelve miles distant from Paris, into a palace to accommodate himself in royal fashion and provide lodging for his courtiers who were otherwise forced to lodge in town. Forced is the correct term, because Louis expected his courtiers to be in attendance upon him nigh-constantly, and there were real costs associated with ignoring the king’s wishes in this regard, for if a rarely-seen courtier requested a favor, Louis would brush them off and claim not to know them altogether because he had not seen them at Versailles. It’s like giving the silent treatment to someone who once snubbed you who later comes looking for a favor, if by you giving them the silent treatment it would crush their dreams and completely destroy them and their family in society.

Louis XIV, affable but absolutist, needed a way to keep his courtiers in line: under his eye, unable to plot against him politically in Parisian establishments, bound to him financially. As such, in 1661, he began the process of transforming the hunting lodge of his father at Versailles, twelve miles distant from Paris, into a palace to accommodate himself in royal fashion and provide lodging for his courtiers who were otherwise forced to lodge in town. Forced is the correct term, because Louis expected his courtiers to be in attendance upon him nigh-constantly, and there were real costs associated with ignoring the king’s wishes in this regard, for if a rarely-seen courtier requested a favor, Louis would brush them off and claim not to know them altogether because he had not seen them at Versailles. It’s like giving the silent treatment to someone who once snubbed you who later comes looking for a favor, if by you giving them the silent treatment it would crush their dreams and completely destroy them and their family in society.

But there were real costs associated with lodging at Versailles as well, as Louis intended. Peer(age) pressure kept nobles spending on the trappings of nobility: elaborate carriages, richer clothing, finer horses, and this necessarily increased their financial dependence on the king. Louis de Rouvroy, Duke of Saint-Simon and memoirist, described Versailles as a gilded cage for the king to contain the formerly troublesome high nobility.

Not just contain, because as I said, these persons were also expected to serve him, daily, ritualistically. Louis’ day began with the lever ceremony in which nobles are admitted throughout his rising and dressing process according to their rank to observe and assist him rise and dress and occasionally make a request of him. All told, the number of spectators admitted to this ceremony numbered around 100, or about the amount of guests at a medium-size wedding in the United States. Even if he’d already arisen to hunt, Louis would return to bed for the start of the lever; attending upon him was their ceremonial duty and it was his ceremonial duty to be there to be attended upon. In the evening came the coucher, in which the king is ceremoniously put to bed, nobles filtering out until Louis was left alone in the room save for the attendant who would pass the night by his bedside, an extremely prestigious position due to its intimate nature.

And throughout Louis XIV’s clockwork reign, there was constant construction at and around Versailles, the business of raising a palace to suit the exacting tastes of its monarch and moving hundreds of nobles and their entire entourage into town. Rooms were created and also demolished, and Louis spared no expense nor tactic when it came to securing what he desired, as the king’s minister of finance, Nicolas Fouquet, came to find out. In 1661, Fouquet threw a party to show off his new château, Vaux-le-Vicomte, to his peers and, of course, to the king. At the time, Versailles was yet a hunting lodge and Vaux-le-Vicomte was finer than any residence of the king, in Paris or otherwise. In retaliation for this embarrassment, Louis had Fouquet imprisoned for the rest of his life with no trial, and immediately hired the architect, garden designer, and muralist at Vaux to begin construction at Versailles, telling them, “You can judge, gentlemen, my esteem for you, since I am confiding in you the most precious thing in the world to me, my glory.”

They took the task seriously (I imagine they had some idea of what happened to their last boss), and with the sun king as their inspiration, devised a celestial palace with planetary salons and large bodies of water oriented to capture the sun. An angel holds a portrait of the king and a banner which proclaims, “World, come and see what I see, And what the Sun admires; Rome in one palace, in Paris an Empire, And all the Caesars in one King.” Modest.

Chapel. Constructed in 1710, a mere five years before the end of Louis XIV’s exceptionally long reign.

Chapel. Constructed in 1710, a mere five years before the end of Louis XIV’s exceptionally long reign.

Salon of Hercules. Louis XV used this as a ballroom, Louis XVI used it to receive foreign ambassadors.

Salon of Hercules. Louis XV used this as a ballroom, Louis XVI used it to receive foreign ambassadors.

This squinting camel knows what you did. Yeah, you.

This squinting camel knows what you did. Yeah, you.

Salon of Abundance.

Salon of Abundance.

Salon of Venus. Sculpture of Louis XIV and it’s probably the influence of those great accessories (are you kidding me with those lion gladiator sandals?) but he is definitely as smoking hot as the sun here.

Salon of Venus. Sculpture of Louis XIV and it’s probably the influence of those great accessories (are you kidding me with those lion gladiator sandals?) but he is definitely as smoking hot as the sun here.

Salon of Diana. Named after the goddess of the hunt. Louis XIV would use this room for billiards at soirees.

Salon of Diana. Named after the goddess of the hunt. Louis XIV would use this room for billiards at soirees.

Center: Louis XIV in white marble. All the marble in this room is original to the palace’s construction, created when marble was a novelty.

Center: Louis XIV in white marble. All the marble in this room is original to the palace’s construction, created when marble was a novelty.

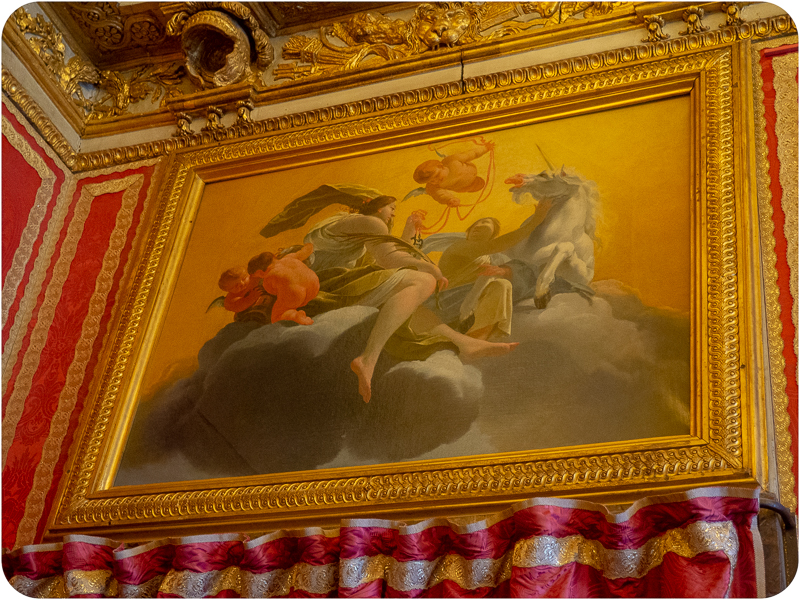

Salon of Mars. Originally intended for guards, hence the theme of war lest they get too soft from looking at paintings of cherubs and unicorns. But it looks like a few sneaked in, anyway.

Salon of Mars. Originally intended for guards, hence the theme of war lest they get too soft from looking at paintings of cherubs and unicorns. But it looks like a few sneaked in, anyway.

Salon of Mercury. Originally the furniture in this room and others were solid silver. There were silver benches and stools, silver mirrors, silver candelabras, silver tubs for the orange trees which perfumed the rooms, and more. It all amounted to twenty tons of metal, but Louis XIV sent it all to be melted down in 1689 to finance the War of the Grand Alliance.

Salon of Mercury. Originally the furniture in this room and others were solid silver. There were silver benches and stools, silver mirrors, silver candelabras, silver tubs for the orange trees which perfumed the rooms, and more. It all amounted to twenty tons of metal, but Louis XIV sent it all to be melted down in 1689 to finance the War of the Grand Alliance.

Salon of Apollo, god of the Sun and Louis XIV’s life inspiration. It’s the extremely rich equivalent to plastering your room in posters of your hero.

Salon of Apollo, god of the Sun and Louis XIV’s life inspiration. It’s the extremely rich equivalent to plastering your room in posters of your hero.

Salon of War. Center, relief of Louis XIV.

Salon of War. Center, relief of Louis XIV.

Mantle detail, Salon of War.

Mantle detail, Salon of War.

Versailles is exquisite, and each room is so ornate that no photo can truly do it justice. Before our trip to France, Jason and I agreed that we wanted to purchase and bring a 360° camera to capture something closer to the whole of that moment in time in that exact location in these magnificent places. As Jason was to be in charge of the 360° camera, he was responsible for learning its operation and he elected for the “trial by fire” method which means that I am in possession of a veritable treasure trove of mostly truly horrible 360° videos, a good number of which are an immersive view of his coat pocket. The camera perspective shifts wildly while filming, challenging even the strongest stomachs. Sometimes, the video will dip toward Jason’s phone as he uses the hand holding the 360° camera to tap something. In their stitched view, the videos are grainy and mediocre. In their flat view, it looks like missing footage from The Blair Witch Project, except always with a finger across the bottom of the lens. It’s not just him–I took a few equally horrible 360° videos and since they do capture everything around them, I can no longer be in denial about the state of affairs on the top of my head and find Louis XIV’s “quirk” of never appearing before anyone without his wig eminently more reasonable.

You can do this walkthrough yourself at Google Arts & Culture!

The Hall of Mirrors. Nearly 240 feet long and constructed when mirrors were rare and costly instead of the technique crummy apartments use to make their rooms look larger.

The Hall of Mirrors. Nearly 240 feet long and constructed when mirrors were rare and costly instead of the technique crummy apartments use to make their rooms look larger.

Ceiling detail in the Hall of Mirrors.

Ceiling detail in the Hall of Mirrors.

I require these window latches for my home immediately.

I require these window latches for my home immediately.

This golden balustrade, originally a one-ton piece of silver, is the line in the king’s bedchamber that the nobility could approach, but not cross. The velvet rope is the line for commoners.

This golden balustrade, originally a one-ton piece of silver, is the line in the king’s bedchamber that the nobility could approach, but not cross. The velvet rope is the line for commoners.

I don’t have any historical tidbits about Louis De Bourbon and I’m not going to look any up and pretend I even know who he is, I just think his outfit looks like he’d make an excellent pirate.

I don’t have any historical tidbits about Louis De Bourbon and I’m not going to look any up and pretend I even know who he is, I just think his outfit looks like he’d make an excellent pirate.

Even if I’d gotten the audio tour guide I doubt they would have addressed the burning questions I have, like what exactly are these things? Werecats?

Even if I’d gotten the audio tour guide I doubt they would have addressed the burning questions I have, like what exactly are these things? Werecats?

Five million visitors a year passing over exactly the same spot does a number on your stonework.

Five million visitors a year passing over exactly the same spot does a number on your stonework.

The Gallery of Great Battles, constructed after the time of even the last king Louis of France, in 1833.

The Gallery of Great Battles, constructed after the time of even the last king Louis of France, in 1833.

The guard room anywhere else would be a damn nice room, with its wainscoting and gilding and parquet floors and natural light streaming in through the windows, but compared to the opulence on display everywhere else in the palace, this room looks like a dog kennel.

The guard room anywhere else would be a damn nice room, with its wainscoting and gilding and parquet floors and natural light streaming in through the windows, but compared to the opulence on display everywhere else in the palace, this room looks like a dog kennel.

The day was drizzly and miserable, and neither of us felt much like walking the whole of the expansive grounds on their off-season. Even the courtyard of a king couldn’t compare to the lure of a croissant.